Held in Trust

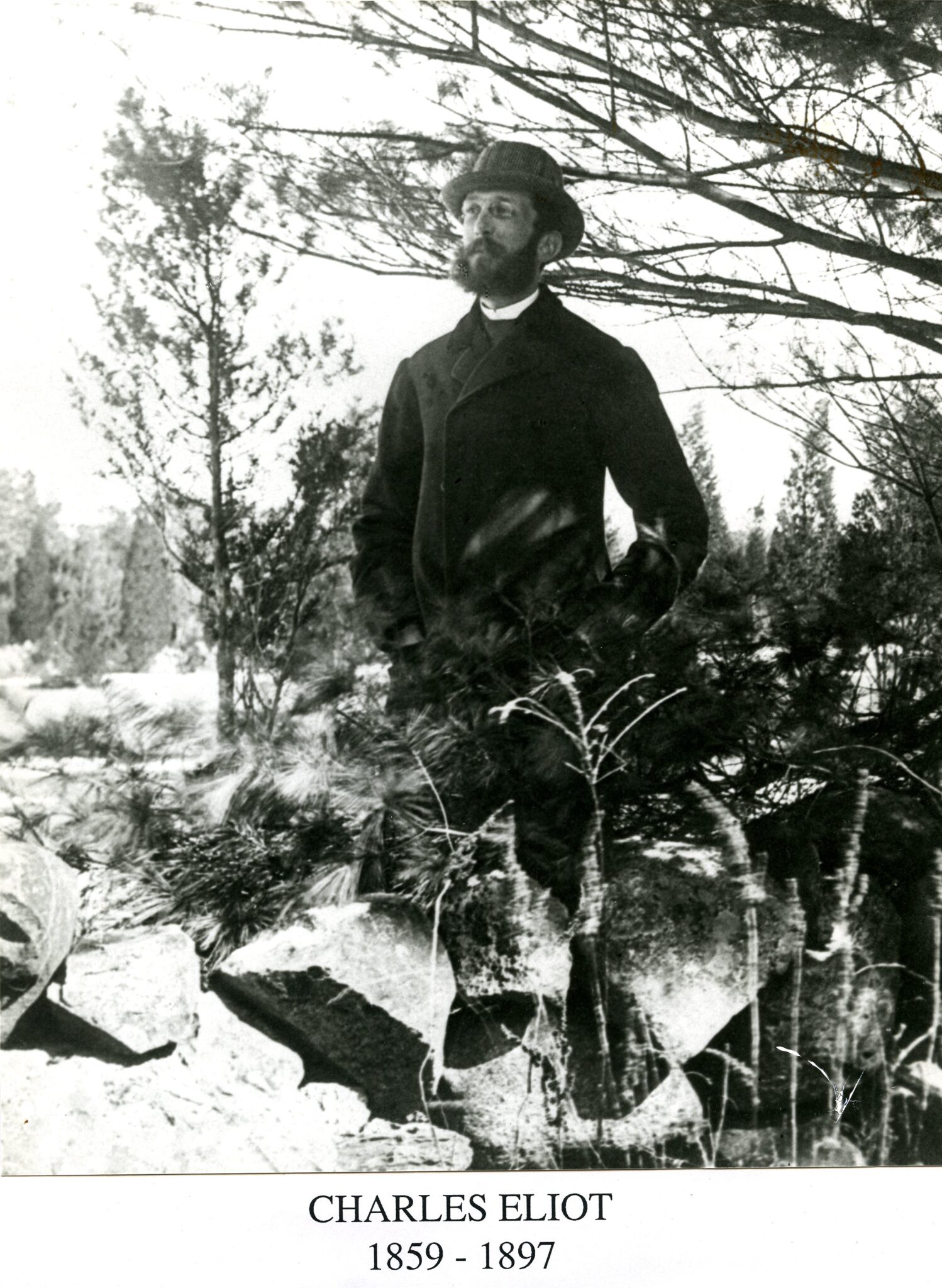

Charles Eliot and the Founding of the Trustees of Public Reservations

By Keith N. Morgan

“…this different end might better be attained by an incorporated association, composed of citizens of all the Boston towns, and empowered by the State to hold small and well-distributed parcels free of taxes, just as the Public Library holds books and the Art Museum pictures—for the use and enjoyment of the public. If an association of this sort were once established, generous men and women would be ready to buy and give into its keeping some of these fine and strongly characterized works of nature; just as others buy and give to a museum fine works of art.”

With these words, the 31-year-old landscape architect Charles Eliot (1859-1897) launched the idea of a statewide, nonprofit organization to hold lands of scenic, natural, and historical significance in an article about the preservation of the Waverley Oaks, a stand of aboriginal trees on the border between Belmont and Waltham, west of Boston. The article appeared in Garden and Forest, a journal of horticulture and forestry, on March 5th, 1890. He clipped the article and pasted it into a scrapbook—that he kept for the remainder of his short life and is now held in the archives of The Trustees—of articles relating to the establishment of the both the Trustees of Public Reservations in 1891 and the Boston Metropolitan Park Commission in 1892-93.

These two revolutionary schemes for the preservation and management of open lands were linked in Eliot’s thinking from the beginning, and became models for emulation across the United States and beyond. Today, 125 years later, we can celebrate the dynamic vision of the founders and the challenges they established for land stewardship.

From distinguished Massachusetts lineage, young Charles had experienced a peripatetic childhood, as his father, Charles W. Eliot, moved the family around Europe to observe current scientific laboratory and educational practices after losing a promotion in the chemistry department of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. By 1869, Professor Eliot had returned from Europe to accept the post of president of Harvard College. That year was also traumatic for young Charles, age 10, when his mother died after a long battle with lung congestion. With his father consumed by his new duties, relatives took over the supervision of Charles and his younger brother. He dutifully trained to enter Harvard College, an institution that his father was radically changing, although the son was somewhat directionless and disengaged. He spent two college summers camping on Mount Desert Island in Maine, organizing classmates to assist him in recording the island’s natural history.

Following graduation, he began to consider a career in the new field of landscape architecture, first by taking courses in agriculture and horticulture at Harvard’s Bussey Institute. Then, in 1883, he became the first apprentice of Frederick Law Olmsted, the nation’s leading landscape architect, who had relocated from New York City to suburban Brookline, Massachusetts, to supervise his designs for the Boston Park Commission. After two years in this apprenticeship, Eliot resigned to follow a professional grand tour, first of sites along the East Coast of the United States and then in Europe.

In addition to long hours of reading the literature of landscape architecture and history in the library of the British Museum in London, Eliot pursued an itinerary of key sites and individuals in his newly chosen profession. These included contact with leading figures in England, such as James Bryce, an Oxford historian who was also a leading member of Parliament and author of early land preservation legislation, and Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, the Secretary of the Lakeland Defense Association in England’s Lake District, one of the first advocacy organizations for public access to private land. These contacts, as well as months of travel through Europe, made him the best-educated and most-connected American member of his profession when he returned to set up a private practice in Boston in 1887.

Initially declining an invitation to join Olmsted’s firm, Eliot began to work on projects that allowed him to develop a unique vision of landscape architecture, preservation, and history. He also began to write for both the profession and the public at large on issues relating to park design, landscape history, and forest conservation, based on his European readings and travels. He joined a network of key individuals in the Boston area—including Olmsted; Charles Sprague Sargent, director of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University and publisher of Garden and Forest; and Sylvester Baxter, a Malden-based journalist for the Boston Evening Transcript, who would become a co-conspirator in the creation of the Boston Metropolitan Park Commission.

Although The Trustees of Public Reservations, a name later reduced to just The Trustees of Reservations, was initially conceived as a statewide enterprise, Eliot’s earliest writing were focused on the area of Metropolitan Boston, a web of communities where he saw the open landscape being rapidly eliminated. In that same article on the Waverley Oaks, he noted: “Within ten miles of the State House there still remain several bits of scenery which possess uncommon natural beauty and more than usual refreshing power. Moreover, each of these scenes is, in its way, characteristic of the primitive wildness of New England, of which, indeed, they are surviving fragments.” While Eliot may have been slightly romantic in assuming these elements of landscape were untouched by human occupation, he evinced passion about the need to set these aside these spaces for enjoyment of the rapidly urbanizing population of the capital region.

On the same day that the article appeared, Eliot wrote to both Charles Sprague Sargent and to George C. Mann, the president of the Appalachian Mountain Club (AMC), to enlist their support in organizing a meeting of influential figures from across the Commonwealth to discuss the launching of this association. Eliot saw the AMC membership as the initial foundation of individuals who shared his goals of landscape conservation, but he quickly capitalized on both family and professional associations to rally the troops to his concept. With lightning speed, he assembled representatives of the trustees from the Museum of Fine Arts, the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Essex Institute, and Harvard College. An organizing meeting of the AMC on April 2nd prepared the groundwork for a larger meeting of important citizens at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on May 24, 1890, with approximately 100 present.

Throughout these months, Eliot continued to write reports and correspond with individuals from across New England and the country about this idea. Multiple committee meetings led to the drafting of legislation that was passed by the Massachusetts legislature and signed by Governor William Eustis Russell on May 21, 1891, 14 months after the initial idea had been launched. Eliot became the first secretary of The Trustees of Public Reservations, although he still had related business that he wanted to accomplish.

Eliot had initially envisioned a public authority that would address the problem of land conservation in the metropolitan district of Boston. Just as he had used the Appalachian Mountain Club as a base from which to launch The Trustees, he now saw this statewide organization as a foundation for lobbying the City of Boston and its surrounding suburbs to create a unified district for the preservation and development of open space. He used the existing concept of a metropolitan water and sewer district to convince legislators, politicians, and citizens of these communities that unified action, funding, and coordination would work to the benefit of “all the Boston towns.” That required slightly more maneuvering by Eliot, Sylvester Baxter, and others, but a preliminary metropolitan park commission was established in 1892, and legislation approved in 1893 created the permanent Boston Metropolitan Park Commission, the first regional landscape planning authority in the United States.

Both The Trustees and the Metropolitan Park Commission (MPC) became important models, the former inspiring the creation of the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest and Natural Beauty in Great Britain in 1895, and the latter becoming the template for metropolitan areas across the United States. But on March 25, 1897, just four years after these had occurred, Charles Eliot died at age 37, the victim of cerebral meningitis contracted while working on a park system for Hartford, Connecticut. His stunned father attempted to secure the legacy of his elder son by assembling a collection of his writings and providing a biographical framework in Charles Eliot: Landscape Architect, published in 1902. In 1898, the MPC had also published posthumously Eliot’s blueprint for the development entitled Vegetation and Scenery in the Metropolitan District of Boston, displaying a scientific attitude toward the public domain and its management.

Today, Eliot’s ideas of both a private statewide association and a public metropolitan authority working to ensure the preservation and management of lands of scenic and natural beauty provide a democratic asset available to residents of the Commonwealth. For all of us, it's an inheritance of enormous importance and lasting value.

This piece was first published in 2016 in The Trustees at 125: A Commemoration.